89. Durrington Walls Was No Village. No houses have been found inside it. This Geometric and Astronomical Wonder Was The Mother of Stonehenge. Go Tell English Heritage!

The much-derided Beaker people, often overlooked in archaeology, were the masterminds behind the architectural marvels of the Durrington Walls henge, its timber egg-shaped circles, Woodhenge and Stonehenge. Their designs were not mere structures but a testament to their profound understanding of celestial alignments and intricate rituals. They showed a keen awareness of how altitude influenced astronomical alignments, particularly when observing the mid-June sunset vanish behind the distant rim of Durrington’s bowl-shaped valley from a bend in the River Avon. This elevated perspective shifted the sunset several degrees further south than at Stonehenge - a significant deviation. The likely azimuth was around 300 degrees.

Durrington’s solstice sunset was intense, a spectacle that occurred only on the summer solstice eve. Regrettably, the modern landscape, especially the construction of the Countess Road, has obscured the view of the solstice, which could once be seen from the River Avon.

Ashes from a cremation, alongside a geometric timber egg known as the Southern Circle, were transferred to what Wainwright wrongly called a ‘Midden’ and Pearson a 'house,' and were enriched with many beaker sherds. In fact, the bones from the pyre had been carefully sifted and taken to be buried in the Aubrey Holes of Stonehenge. This left some very restless spirits behind, who wished to rejoin them, as was the intention.

Durrington’s numerous radii are based on Avebury’s 750 MY moon antenna, lending further credence to growth symbolism.

In mid-June, high-intensity sunlight entered the Southern Circle, a timber egg, acting as a fertilising agent, and its progress was restrained by what Wainwright called a facade. At the same time, there was hopeful anticipation that the contents of the Midden and starlight from Thuban, the north star in 2,500 BC, would be added to the mix. In the grand scheme, only the spirits of the dead would be permitted to exit the egg and travel the Avon Umbilical to reach Stonehenge.

Along this path, those charged spirits would pass a ‘Sex Pit,’ a symbolic representation of fertility and life, placed, as you might expect, at the entrance/exit of the Durrington womb. The pit contained a natural flint formation resembling a female pelvis, several pairs of testicles, and three chalk penises, all of which symbolised the cycle of life and the Beaker People's deep reverence for fertility.

The River Avon, central to the Beaker People's rituals, was not merely a physical entity but a tangible link to Stonehenge. As it flowed south towards Stonehenge, the Beaker People would reverently cast masses of flesh, primarily from nine-month-old piglets, into it. This act transformed the Avon into an umbilical cord, a profound connection to Stonehenge. The ritual was a testament to their deep reverence for the river and their belief in the Neolithic moon as a female deity. It was a cornerstone of their intricate and profound belief system, woven into their rituals and spiritual practices.

It was hoped that the spirits held in the Midden might, on the summer solstice eve, penetrate the ‘Southern Circle,’ which, incidentally, the beaker people regarded as a zygote, and assist in its fertilisation before following the Avon to reclaim their impounded bones at Stonehenge.

Despite several TV productions, no houses were built within the enclosed arena at Durrington Walls. However, archaeologists discovered a mini-henge in 2005.

Other monuments with profound growth symbolism include Avebury Henge, Mount Pleasant Site IV in Dorset, Windmill Hill causewayed enclosure, and Longstone’s enclosure at Beckhampton, all of which testify to the Beaker people's deep-rooted connection to fertility and growth in their rituals.

Finally, the image above shows the nearby Woodhenge as an autonomous monument. It is not connected to Stonehenge via the River Avon, as suggested on Channel 5 TV in "Stonehenge: The Discovery. 21.00 1st March 2024." This programme mistook Woodhenge for the Southern Circle Zygote. Furthermore, as I told the Open University as long ago as 2007, the Woodhenge egg points at the moon, not the sun!

90. DURRINGTON WALLS SOUTHERN CIRCLE PROVES THAT BEAKER PEOPLE HAD THE MEGALITHIC YARD, UNDERSTOOD PYTHAGOREAN GEOMETRY, AND COULD COUNT!

This intricate Pythagorean geometry is a fascinating puzzle that stands as a testament to the advanced mathematical understanding of ancient people and might never have been resolved without the help of maths.

The Southern Circle is intricately connected to Stonehenge via the river Avon and Stonehenge Avenue. Its outer Ring A is based on the same three-ring principle as the nearby Ring A of Woodhenge, which overlooks it, and the beautiful stone ring of Callanish on the Scottish Island of Lewis.

Rings B, C, and D were relatively straightforward to solve. However, the real breakthrough came when it was found that these three rings adhered to a complex mathematical series. This series enabled the solution to the inner Rings E and G, which were more challenging.

Below is the series B to G in Megalithic Yards - the Stone Age standard of measure. It’s a complex system that reveals the intricate mathematical thinking of our predecessors….

Small Radiuses: Ring B (19), minus 3.5 gives Ring C (15.5), minus 4 gives Ring D (11.5), minus 4.5 gives Ring E (7), and minus 5 gives Ring G (2)

Large Radiuses: Ring B (21), minus 3.5 gives Ring C (17.5), minus 4 gives Ring D (13.5), minus 4.5 gives Ring E (9), and minus 5 gives Ring G (4)

Ring F - the Yolk - is circular at 13 MY diameter. Strangely, Egg G is inside the yolk! Perhaps Egg G was thought to be the germ awaiting fertilisation!

All eggs share the same major and minor axes. The major axis is strategically positioned to intersect with the incoming mid-June sunset.

91. Durrington Walls, the mother of Stonehenge, is seen above with the geometric moon-egg, Woodhenge.

Before English Heritage placed its vastly exaggerated and false information boards alongside Woodhenge and Durrington Walls, visitors to the more obvious Woodhenge site would often ask, “Where is the massive henge known as Durrington Walls?” Both monuments are pictured above. With concrete posts representing what were once massive tree trunks several feet tall, Woodhenge is seen entering the picture from the right.

The snow-covered horizon marks Durrington Walls’ far bank. Its north-western bank, which Beaker Folk built in 2,630 BC, can be seen on the left, but it’s not snow-covered in this picture.

People were attracted to Durrington’s valley, or combe, by the elevated north-western bank, which, even today, delays the summer solstice sunset, which has a completely different azimuth to that over flat ground.

The snow was left behind by the ‘Beast-from-the-east’ - a cold snap that came across from Siberia in 2018.

Durrington Walls’ near bank, or what is left due to many years of ploughing it flat, is just beyond the line of parked cars. This, too, is marked with snow. Beyond the trees to the right of the picture can be seen another section of Durrington Walls' bank. This is also highlighted with snow.

Cutting through those trees is the Countess Road, built post-1968. This new highway is elevated several feet above the pan-shaped valley, which early folk had cordoned off to make Britain’s largest henge. Note the blue farm vehicle parked beneath the new road's embankment because that vehicle very nearly marks the centre of the timber egg known as the “Southern Circle.”

Professor Wainwright discovered the Southern Circle in 1966/68 when excavating in advance of the Countess Road, which replaced the old road with its dangerous bend that caused several accidents. Unfortunately, Wainwright's excavation exposed only two-thirds of the Southern Circle, and even that is lost to us beneath the embankment of the new road. Thankfully, the remaining one-third was investigated by archaeology and the Time Team in 2005, but not with the same thoroughness as Wainwright’s dig.

Note the red vehicle on the extreme right of the above picture because the following photo was taken near it.

92. The old road, little more than a track, can be seen to pass over Durrington Walls' denuded bank before dipping through the centre of the henge.

Much of Durrington Walls has been completely flattened due to many years under the plough. This was fortunate in some ways because loosened chalk and hill-wash colluvium covered the monuments lower down and protected them - especially the Southern Circle of timber.

Prehistoric remains at the top of the combe lost much of this protective cover and were not so lucky.

Imagine what the above landscape looked like 4,500 years ago, with a ten-foot-high bank of gleaming white chalk blanking out most of the sky.

Note the footpath in the right foreground because the following photograph was taken while standing on this footpath.

93. The henge and the Southern Circle of timber were connected to the river Avon via an avenue of hard-packed chalk and flint. The river can be seen behind the van and through the trees that grow along its banks. My impression of the Avenue is superimposed on the photograph. The steep slope should give you the idea that something was meant to exit the henge by sliding down it.

The Stonehenge Riverside Project, which was started in 2003, found five prehistoric houses or huts flanking this avenue. All of them were found buried beneath Durrington Walls' bank. These houses were small affairs measuring approximately six megalithic yards square. Their positions are marked in the above picture with small splodges of snow, which can be seen beyond the row of trees.

Hoping to solve the age-old mystery of when folks had gathered to celebrate at Durrington Walls - i.e., was it summertime or winter - one of Britain’s top astronomers, Professor Clive Ruggles of Leicester University, was invited to prove what the Avenue pointed at in 2,500 BC. Clive proved it to aim at the mid-June sunset. This agrees with the astronomer Professor John North, who measured it years ago.

So, nine-month-old piglets collected from all over the country were destined to be slaughtered as the sun set beneath Durrington Walls' western bank at the close of summer solstice day. Piglets were chosen because nine months corresponds to the human female gestation period.

*****

If you want a job done right, do it yourself. So, on Solstice Day, 21st of June 2018, you might have seen me standing close to the blue tractor, which nearly marks the position of the Southern Circle.

The actual place is marked by a drain that runs beneath the Countess road and prevents the valley from flooding. And that is where I waited for the summer sunset.

It was a bit of a shock to find that the sunset could no longer be seen while standing by the drain because bushes growing alongside the old road were blocking the view. So, a hurried leaping of a few fences was made to get into a better position.

Watching the sun go down inside the Durrington Walls henge was an unforgettable experience because of the feeling I got when climbing out of the henge to find it was still daytime at Stonehenge.

94. My photograph of the setting summer solstice sun seen from inside the Durrington Walls Henge. 21 June 2018.

A beaker burial, dated to 2,630 BC, was found beneath the bank to the left of the sun. Professor Stuart Piggott put the hex on this early date with his anti-beaker-person bias because these early geometers might have come from Germany.

One beaker man, identified by his brachiocephalic skull, was discovered in the long barrow of Belas Knap, which dates to 3,300 BC. He was found guardian-like, protecting several children of increasing ages, which I once described as like 'Ovaltine's. This is enlightening because the cremated bones recovered from Stonehenge's Aubrey holes also wished for something to grow. These were as follows... a foetus, an infant, a young child, an old child, a teenager, and 21 adults.

Please permit me to tell you what happened to the Stonehenge dead, apart from an inhumation placed on Stonehenge’s secondary axis.

The Stonehenger's were cremated inside the Durrington Walls Henge on funeral pyres adjacent to the timber egg known as the Southern Circle. When cool, the bones were separated from the ashes and taken 1.8 miles overland to Stonehenge. Meanwhile, people's ashes were placed inside a so-called ‘Midden’ attached to the northeast side of the egg.

Professor Wainwright believed the Midden to be ceremonial. He also stated it was too large (6.7 by 12 metres) to be roofed, especially since it lacked a central post to support one. So, the Midden was not a house, hut, lodge, or building.

The midden was full of black ash, a third of a meter thick, and held almost 50% of the total beaker pottery sherds found on the site. The people who placed the ashes in the Midden believed it contained the spirits of the dead. This ash was carbon-dated, but we will dismiss the late date because archaeologists had proved untrustworthy well before they excavated Durrington.

The Midden was built like an eye dropper, designed to pour its spirit-rich contents into the egg at the same time as the mid-June sun seared through the egg on its way to the river Avon. But first, this spirit-laden and fertile sunlight passed over a Sex-Pit, which contained a female pelvis of natural flint, several pairs of balls, and an erect penis of flint.

These spirits then travelled along the Avon until they met up with Stonehenge Avenue, located on the north bank of the river by the West Amesbury Henge of timber. Then, by following Stonehenge Avenue, those spirits finally arrived at Stonehenge to be reunited with their bones.

Like Avebury’s West Kennet Avenue of stone, the River Avon was an umbilical cord to prehistoric folk.

One final thought on the problem of broken pottery. Imagine smashing a beaker pot and placing one sherd in the midden, then sending a matching sherd away to Stonehenge. Neolithic folk are famous for shifting stuff around.

95. This is a plot of the posts, which once held massive timbers that made up the Southern Circle. First, note that several posts were placed in threes to represent the family.

Resolving the underlying geometry of the Southern Circle would always require much work and an intimate knowledge of the Stone Age mind.

96. The outer Ring A. Durrington Walls’ outer ring, or egg, is type-style to the nearby outermost ring of Woodhenge and the single ring of Callanish on the Scottish Isle of Lewis.

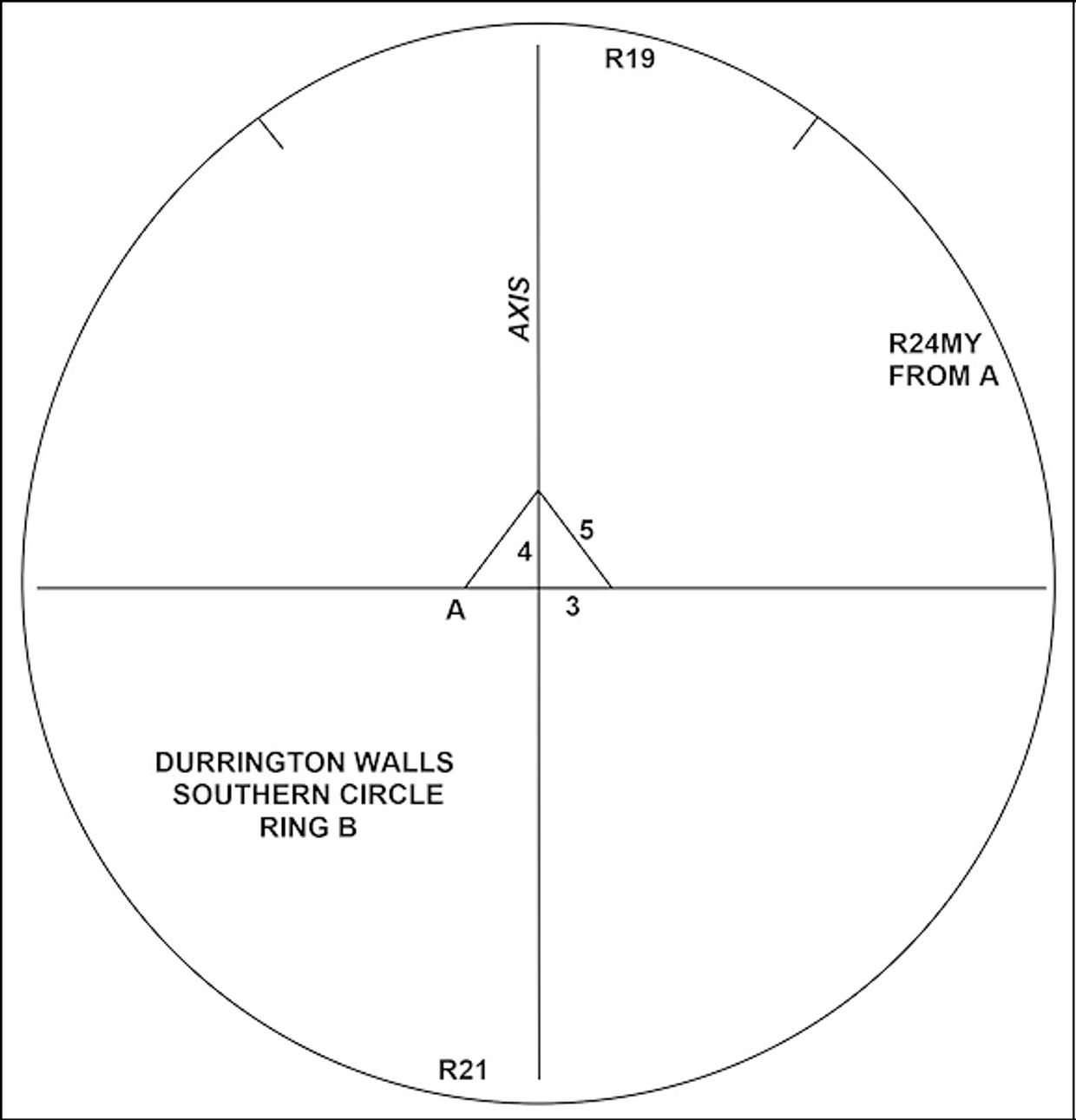

97. Ring B. Perfect geometric egg based on a pair of 3:4:5 Megalithic Yard triangles.

98. Ring C. Perfect egg based on identical 3:4:5 triangles.

99. Ring D. Perfect egg, again based on identical 3:4:5 Megalithic Yard triangles.

Furthermore, eggs B, C, and D obey the simple series...

Small radiuses: Ring B (19), deducting 3.5 gives Ring C (15.5), deducting 4 gives Ring D (11.5.)

Large radiuses: Ring B (21), deducting 3.5 gives Ring C (17.5), deducting 4 gives Ring D (13.5.)

Astonishingly, this series predicts the sizes of eggs E and G.

100. Rings E and G. Starting from the known Ring D…

Small radiuses: Ring D (11.5), deducting 4.5 gives Ring E (7), deducting 5 gives Ring G (2)

Large radiuses: Ring D (13.5), deducting 4.5 gives Ring E (9), deducting 5 gives Ring G (4.)

Ring F - the yolk - is circular at 13MY diameter. This agrees with Professor Wainwright.

101. Putting it all together. North is at the top.

The eggs of the Southern Circles all share the same major and minor axes.

Uniquely and precisely as predicted, the smallest egg is inside the yolk.

The major, or central axis, cuts through the incoming summer solstice sunset, just like the moon-aligned outer face of Stonehenge’s Heel Stone.

Apart from a hearth, what went on at the centre of this device?

102. This is the ideal time and place to announce my newest acquisition. The source is on page 53 of "Megalithic Remains in Britain and Brittany" by Thom and Thom.

This is a rubbing of a cup and ring pecked on a stone in the garden of Cardrones House - somewhere in Scotland. Like Durrington's Southern Circle, the eggs are based on 3:4:5 perfect triangles and increase in size arithmetically. The pecked image is tiny by comparison, measured in Megalithic Inches. (One megalithic inch is equal to 0.8166 imperial inches)

A quote on Thom’s Perimeters:

"It is evident that it was considered important to have the perimeters as multiples of 2.5 units, and we suggest that this rule was given priority to the extent that it was allowed to control the radii, otherwise why did the designers use 4.625 MI for the largest radius?"

Unquote:

Answer: The designers did not. Thom and Thom stretched a point with the outer egg to make it conform to their unrealistic perimeter theory.

103. "Mossyard pecked stone," again from somewhere in Scotland. It is on page 52 of "Megalithic Remains in Britain and Brittany" by Thom and Thom.

Unbeknownst or overlooked by the Thoms and without interest in the hypothesis, these five rings start with a tiny 0.75 Megalithic Inch diameter pecking at their very centre. The rings that follow increase in arithmetical steps of 2.75: first by two circles and then three eggs. The largest circle is, therefore, 5.75 in diameter, not 5.5.

Mossyard is one further example of a monument that expresses growth. But what did prehistoric folks wish to grow? More to the point, what did they place inside the tiny cup for exposure to the sun? Seed of Barley, perhaps? A spoonful of egg yolk? Or might it have been some form of human DNA?

It's easy to imagine taking some eggs from a female's ovary, adding some sperm, and placing the mixture in the cup-shaped depression in the middle of these geometric eggs.

"They would then expose it to sunlight to observe its reaction."

Stonehengeology